GFB News Magazine

Georgia forests could fuel carbon-neutral aviation

Posted on June 3, 2024 8:31 AM

By Jay Stone

Wood was a part of aviation at the start.

The Wright Brothers’ took their world renowned 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk, N.C., on a wooden airframe. Wood has been fashioned into propellers and other plane parts. Howard Hughes’ famous Spruce Goose was an all-wood cargo plane. Australian YouTuber Bobby McBoost has burned wood to fuel a turbojet engine to power an unmanned boat.

Now, there is a move to convert wood into sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), with Georgia Tech researchers chasing optimization.

What’s driving SAF development?

The United States consumed 306.76 billion gallons of petroleum fuel products for all uses in 2022, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency. Of that, the U.S. aviation industry used 24.1 billion gallons or 7.8% of all petroleum fuel products consumed in the U.S. in 2022. Planes in the U.S. used 23.9 billion gallons of kerosene-type jet fuel and 185.6 million gallons of finished aviation gasoline.

Close to one billion gallons of jet fuel were used in Georgia, almost all at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The aviation industry is working to reduce its carbon footprint, in large part by reducing dependence on fossil fuels, specifically in its use of aviation and/or jet fuel.

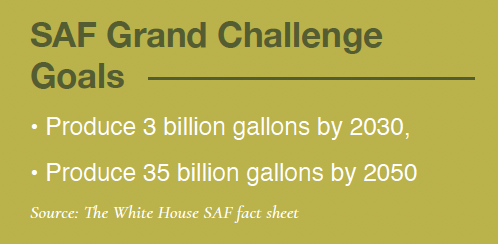

Part of the urgency comes from the federal government’s Sustainable Aviation Fuel Grand Challenge. This challenge aims to scale up SAF production to 35 billion gallons by 2050, with a near-term goal of 3 billion gallons by 2030.

The SAF Grand Challenge is being pursued jointly by the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Transportation, USDA and the Environmental Protection Agency. Producing three billion gallons of domestic sustainable aviation fuel per year will reduce life cycle greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2030, the agencies say.

article continues below

Efforts to make sustainable aviation fuel in Ga.

Efforts to make sustainable aviation fuel in Ga.

Enter the Georgia Tech Renewable Bioproducts Institute (RBI), which is researching ways to better utilize wood, whether it’s from trees harvested specifically to generate fuel or wood waste like scrap lumber from construction or sawdust from sawmills.

“We're looking at what we can do with woody biomass in Georgia and in the rest of the Southeast,” said Dr. Valerie Thomas, Georgia Tech’s Anderson-Interface Chair of Natural Systems and RBI’s lead for sustainability analysis.

The amount of fuel the U.S. aviation industry uses makes for a daunting challenge. Manufacturing of SAF will have to grow on a massive scale before it can meet significant portions of the fuel needs.

There are multiple ways to make jet fuel from plants, Thomas said. One is to produce ethanol and then convert the ethanol to jet fuel.

LanzaJet’s Freedom Pines Fuels facility in Treutlen County is a step in that direction. According to the company, ethanol made using a variety of sources including energy crops, agricultural waste, and municipal solid waste will be transported to the Soperton plant where it will be converted into energy-dense fuel needed to run existing aircraft. LanzaJet says its technology will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by more than 70%.

The Illinois-based company with ties to New Zealand, has amassed support from multiple U.S. government agencies and big business to develop SAF using a variety of ethanol sources.

During Freedom Pines’ grand opening on Jan. 24, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said the facility is an important early step to enable American companies to corner the market on a valuable emerging industry and boost rural communities like Soperton.

“LanzaJet’s facility will help accelerate the SAF industry and provide new economic opportunities for producers for a more sustainable future,” Vilsack said.

Initially, Freedom Pines is expected to produce 10 million gallons of SAF per year, equal to about 1% of the amount of fuel used at Hartsfield-Jackson.

Thomas says another way to make SAF is to take woody biomass, gasify it and make jet fuel from that.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Energy awarded an $80 million grant to AVAPCO LLC, a biofuel, biochemical and biomaterials company with a plant in Thomaston that has been working to produce cellulose and ethanol from wood processing waste since 2009. AVAPCO plans to use the $80 million grant to build a demonstration plant capable of producing 1.2 million gallons of jet fuel annually, plus sustainable material for the rubber industry. The company is a subsidiary of GranBio, a Brazilian company pursuing green technologies.

“There’s several routes to making the jet fuel. Some of the work we're doing is to investigate a few other of these ways,” Thomas said. “And there are also variants: Is there a variant we can do that’s cheaper and better, more efficient? So, some of that work is happening in a hurry right now.”

Benefits for Georgia’s timber sector

For Georgia timber growers, the prospect of adding this new market of aviation fuel to construction and paper uses is welcome news.

.png)

“We know that having more uses for timber has a positive impact on a forest landowner's ability to be able to economically grow timber as a crop,” Georgia Forestry Commission Director Tim Lowrimore said. “For additional markets to be able to come online that are in balance with the existing facilities and existing markets that we have in our state is a win for forest landowners for sure, because it creates additional uses and additional demand for the trees they're growing and sustains their economic viability as a tree farmer.”

Around the Southeast, sawmills and pulpwood mills have reduced production and multiple mills have been shut down altogether, Lowrimore said.

Several factors have contributed to economic difficulties in wood and paper industries, including a push toward using less fiber in retail packaging and using alternative building materials to timber in construction. With flagging demand for paper and wood products, producers need new markets to pursue.

Georgia grows 50% more volume than is used in our state Lowrimore noted, so, there is room for new market opportunities.

To Lowrimore, SAF could mean another plank in the construction of forestry’s overall economy.

“We owe it to forest landowners to be promoting those opportunities and to be making sure Georgia’s at the table and as well-positioned as anybody to participate in those markets as they come online,” Lowrimore said.

Recognizing Georgia timber producers’ need for expanded economic opportunity, the Georgia Senate passed a resolution in March to establish the Senate Advancing Forest Innovation in Georgia Study Committee.

While SAF from wood probably will not replace the standard uses for timber in the near future, Thomas says, “It can be kind of a stabilizing additional product that could be produced in Georgia and in similar areas.”