Ag News

What's that sound? Brood 19 coming up from the ground

Posted on Apr 19, 2024 at 6:03 AM

Any day now, chances are good that residents of 75 Georgia counties will start hearing raucous mating calls of male cicadas calling out to potential mates. These Romeos and their lady friends belong to the Brood XIX (Brood 19) of periodical cicadas, for which a new generation only emerges every 13 years.

Brood 19 males only serenade their ladies during the day. They start their love songs as the sun warms them. If you hear a cicada singing after sunset, that's an annual cicada. Periodical cicadas come out from mid-April to late May. Annual cicadas come out in the summer and fall. Both types of cicadas “sing” by vibrating a membrane on the sides of their bodies.

Dr. Nancy Hinkle, a University of Georgia College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences professor of entomology, expects millions of the Brood 19 periodical cicadas will emerge across Georgia before Memorial Day.

“Brood 19 is Georgia’s only 13-year cicada,” Hinkle said. “It’s part of ‘The Great Southern Brood’ that covers at least a dozen states in the Southeast and is the largest periodical cicada brood in North America.”

Hinkle says you can identify the Brood 19 cicadas by their black bodies, red eyes, and clear, orange-tinted wings. Annual cicadas are larger than periodical cicadas and typically have green bodies with black eyes.

“Periodical cicadas are perfectly harmless. They cannot bite or sting, and they are not poisonous,” Hinkle said.

Photo of Brood 19 cicadas shot in 2011 courtesy of Dr. Nancy Hinkle, UGA Entomologist.

According to research by the University of Connecticut, Brood 19 cicadas appear in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Illinois and Indiana.

Why are Brood XIX Cicadas expected in 75 counties?

Georgians last saw and heard Brood 19 cicadas in 2011. That March and April, UGA Extension entomologists recruited Georgians across the state to watch for the insects and report and document sightings by emailing photographs and/or mailing in specimens. A 2012 report compiled by Dr. Hinkle, Cecil L. Smith and Chip Bates details the efforts made to document where the Brood 19 cicadas appeared in Georgia in 2011.

Georgia residents submitted 1,397 cicada reports with 553 including photographs. More than 600 periodical cicada specimens from 25 counties were donated to the Georgia Natural History Museum in Athens.

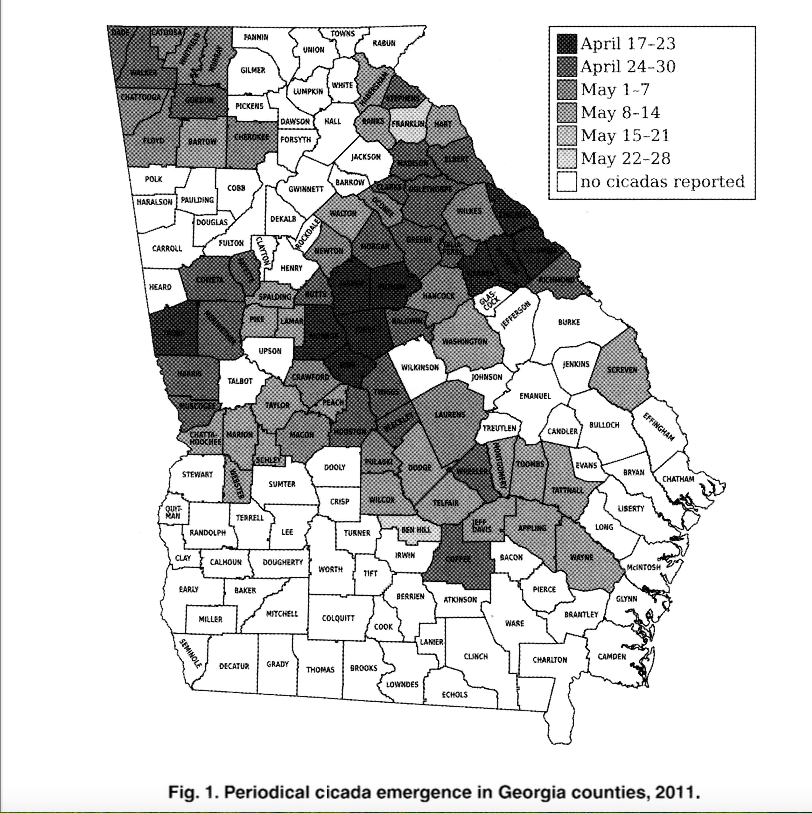

After analyzing all the submitted data, the entomologists determined that Brood 19 cicadas were sighted in 75 Georgia counties based on submitted photos or specimens.

A Georgia map was marked to indicate the date the first cicada sighting was reported for each county. The earliest sighting reported was in Troup County on April 19, 2011. Ben Hill was the last county to report a sighting on May 27, 2011.

Map courtesy of UGA Dept. of Entomology

Before UGA’s 2011 survey, little was known regarding how widespread Brood 19 cicadas were across Georgia. A 1960 report by Hunter and Lund (J. Econ. Entomol. 53:961-63) said Brood 19 cicadas were observed in 14 Georgia counties in the 1959 emergence.

The Georgia Museum of Natural History only had Brood 19 specimens from 17 Georgia counties collected from the 1907 emergence through 1998, the last emergence before 2011.

Hinkle says if a mature hardwood tree wasn’t in place 13 years ago for a female cicada to lay its eggs in, one shouldn’t expect Brood 19 cicadas to emerge this year. If a tree that has been nourishing cicadas was cut down in the past 13 years, it’s likely the cicada nymphs feeding on its roots died.

“No Brood XIX have ever been reported from the Atlanta metro area,” Hinkle said.

It’s believed Brood 19 cicada populations in the Atlanta area died out as trees were cut down, the ground bulldozed, and much of the land paved.

Hinkle says that Brood 19 cicadas only feed on hardwood tree roots. They don't feed on pines because of the turpentine in pine sap.

What happens when Brood 19 cicadas emerge?

After living below ground for 13 years, sucking sap from hardwood tree roots, Brood 19 cicada nymphs (stage between egg & adulthod) emerge, Hinkle says, when soil temperatures reach about 64 degrees F.

Georgetown University insect ecologist Martha Weiss told Scientific American that periodical cicadas appear to count each spring when the xylem sap they feed on becomes briefly richer in amino acids as it moves from the tree’s roots to its canopy.

Hinkle says cicada nymphs typically rise from the ground at night to avoid predators, climb up the nearest tree trunk, and hook their claws into the bark. The skin along the nymph’s back splits, and an adult cicada comes out the slit.

The just molted adult cicada spreads its wings. Once the wings dry, the cicada can fly. By daylight, most of them are flying up into the treetops.

As the sun warms the male Brood 19 cicadas, they begin to sing to attract a female, Hinkle said. Once a female is attracted to a male, she and the male flick their back wings together to mate.

Then the female goes to the end of a tree branch to lay her eggs. She inserts the tip of her abdomen under the bark near the end of a branch and deposits her eggs between the wood and flexible bark. Soon after the adult cicadas die.

A month or so later, the cicada eggs hatch and the nymphs emerge from under the bark and fall to the ground. They burrow into the soil, find a tree root, insert their mouthparts and start sucking root sap.

Brood 19 cicadas live underground feeding on tree roots until it’s time for them to emerge in 13 years. Hinkle says they all come out within a month of one another to maximize the chance of finding a mate.

Enjoy the show

“Periodical cicadas are not pests and there is no need to attempt to control them,” Hinkle says. “Most of them will be dead in a couple of weeks. Use this opportunity to teach your kids and grandkids how cicadas aerate the soil, recycle nutrients, and foster environmental health.”

Hinkle encourages people to watch how their pets respond to the novel cicadas.

“Dogs may gorge on them, vomit them up and then resume eating them,” Hinkle says. “Cicadas make great cat toys; they make noise, they spin across the floor when you bat them.”

And, if you’ve ever thought about eating insects, now is the time.

“Humans can eat cicadas. They’re like softshell crab,” Hinkle says.

She says it’s important to harvest them while they are still soft, before their skin hardens.

“Go out very early in the morning, before dawn, and collect newly emerged adults that have just come out of their nymphal skins,” Hinkle advises. “Remove the legs and wings. Sautee them in garlic butter and serve hot. Recipes can be found online.”

Families can use this rare event as a conversation starter to ask older generations what was happening in their lives in 2011, 1998, 1985, 1972, 1959, 1946, 1933 or 1920. If you don’t have family members who were alive in the earlier years, discuss important U.S. or world events that happened in those years.

After the show

Weeks after all the Brood 19 cicadas have died, Hinkle says to look for tree branch tips that turn brown and fall off. This is where the cicada eggs were laid.

“This is harmless. In fact, it is beneficial to the tree, it’s Nature’s pruning service,” Hinkle said. “Next winter there will be less risk of ice damage because the weak branch tips have been removed.”

Report your Brood 19 sighting

It’s important that Georgians across the state report any sightings of Brood 19 cicadas so there’s an accurate record of the 2024 population for historic and scientific purposes.

The University of Georgia and the University of North Georgia are collaborating on research regarding Brood 19 distribution in Georgia, emergence times, and genetic relatedness of populations throughout the state.

Georgians willing to collect and submit samples of Brood 19 exoskeletons (the hard shell the cicadas emerge from) and/or dead cicadas may mail the specimens to:

Dr. Evan Lampert, 3820 Mundy Mill Road, Oakwood, Ga. 30566.

Georgians willing to collect and submit cicada samples are asked to contact Dr. Evan Lampert at Evan.Lampert@ung.edu for information on how best to submit their specimens.

Another way to report a Brood 19 sighting is via the iNaturalist app (https://www.inaturalist.org ) . You can download the app onto your smartphone or other devices from the Apple app store or in Google Play.

- Categories:

- Tags: